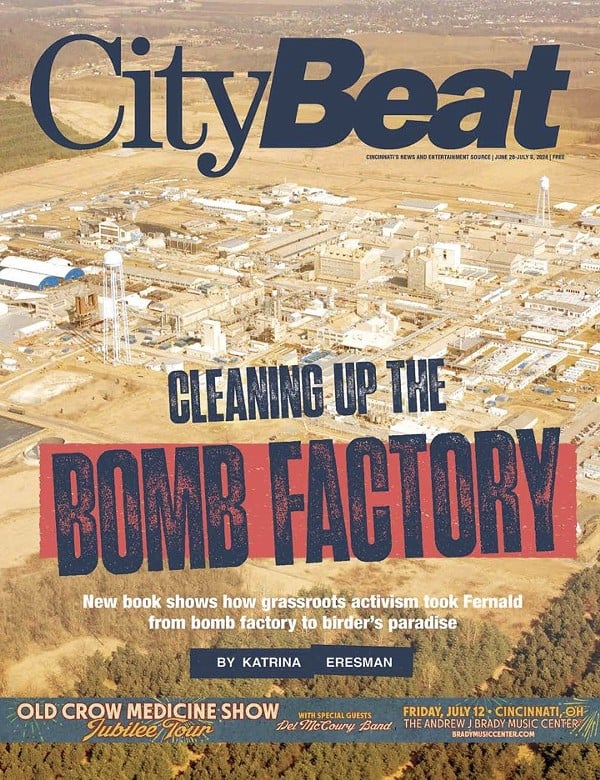

Every year thousands of visitors head to Fernald Preserve to hike, bird watch and learn about the history of this former uranium processing plant. The 1,050-acre nature preserve is located just a short drive from Cincinnati, in Hamilton, and has everything — forests, prairies, wetlands, grasslands and open water. On the eastern boundary of the site, a large on-site disposal facility looms in the distance. This makes it impossible to ignore that what is now a natural sanctuary was once home to the Fernald Feed Materials Production Center, a Cold War-era uranium processing facility.

How did a heavily polluted weapon plant become a healthy destination for outdoor enthusiasts, history buffs and hundreds of species of birds? The short answer is grassroots activism. The long answer — and all of the lessons in environmental activism that come with it — can be found in Cleaning Up the Bomb Factory, the first book by environmental historian Dr. Casey A. Huegel. Within its pages, Huegel explores how the Greater Cincinnati community gained momentum with grassroots activism and a state coalition and managed to be part of the driving force that turned a polluted uranium plant into a nature preserve.

“These stories from history show the power of ordinary people — who may not necessarily have seen themselves as an activist at all — doing really important activism work,” Huegel says. “It shows the power of communities coming together.”

Seeds of distrust lead to community action

Opened in 1951, Fernald Feed Materials Production Center was one of many nuclear weapon production facilities built during the early Cold War in the United States. The Department of Energy chose strategic locations for its low-profile nuclear weapons infrastructures. Ideal locations would be centrally located but inland, so they were less accessible to Soviet bombers. And they could provide some seclusion while still offering the labor force and infrastructure that came with a highly populated area. At 25 miles northwest of downtown Cincinnati, Hamilton, Ohio had it all.

For years, Fernald maintained steady operation, keeping up with the production demands of the Cold War era. The plant consolidated multiple uranium milling, refining and smelting techniques from dispersed locations into one facility. Thousands of working-class people found job security at Fernald, commuting from all over the tri-state area. Since radioactive hazards were unfamiliar and radioactive risks concealed, workers believed their work at Fernald was safer than alternatives, like the coal industry.

Production slowed down during the late 1960s and late 1970s, and Fernald fell out of the limelight. Meanwhile, outside of the plant, antinuclear peace activists were ramping up their efforts.

“In the late 1970s, beginning with the Carter administration but then even more so with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, there's this resurgence in peace activism,” Huegel says.

Groups began forming to unapologetically protest nuclear war and nuclear energy. After the near-disaster at Three Mile Island in 1979, when a malfunctioning pressurized water reactor released radioactive gases and radioactive iodine into the environment, many more people were eager to join the movement. Local antinuclear group Citizens Against a Radioactive Environment (CARE) grew quickly. Amidst the bustle of meetings and research, CARE cofounder Tom Carpenter learned about Fernald, which had been flying under the radar.

After the rediscovery of Fernald, many local activists turned their attention to the nuclear weapons facility in their own backyard. In 1979, Carpenter filed a Freedom of Information Act request to see what he could find within Fernald’s archives. He received boxes of hand-censored documents that he could read by holding the pages to the light and discovered that over 7,000 pounds of radioactive materials had been released into the air and the Great Miami River between 1962 and 1979.

“[That] gave some concrete evidence that there are accidents at these plants,” Huegel says. “There is environmental contamination. And the Department of Energy's claims that everything's under their control and perfectly safe … those were not true claims.”

Over the next few years, Cincinnati antinuclear peace activists maintained their momentum. In the summer of 1983, on the 38th anniversary of the world’s first nuclear explosion in Japan as part of the Manhattan Project known as “Trinity,” activists gathered at Fernald. The “Trinity Day” protest included members of the Oxford Citizens for Peace & Justice, the Ohio Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign, and the American Friends Service Committee. Their peaceful demonstration, followed by the arrests of protestors, brought Fernald to the public’s attention once again.

The following year, in the fall of 1984, an alarm went off at Fernald’s Plant 9. Roughly 275 pounds of uranium had escaped through a broken dust filtration system. On December 11, a reporter named Ben Kaufman broke the news with a front-page story titled “NLO Checking Possible Uranium Leak” in the Cincinnati Enquirer. The Department of Energy responded by hosting a community meeting at Crosby Elementary School, just a mile from Fernald. Hundreds of community members, Fernald workers and environmental activists gathered at the school. Tensions and fears were high as neighbors looked for answers, and hoped for reassurance that their families were safe. But the Department of Energy and Fernald’s contractor, National Lead of Ohio, essentially brushed them off — even though a medical monitoring program designed by the University of Cincinnati in 1990 later revealed that “the Fernald community was at greater risk for urinary cancer, nonmalignant kidney disease, nonmalignant bladder disease and lupus,” Huegel writes.

“Rather than respecting these very valid concerns about public safety and environmental health, [they] basically scoff off these concerns as kind of ridiculous,” Huegel says. “They didn't treat people with respect either, and they weren't forthcoming with information. All those things sowed a lot of distrust.”

The community wanted environmental justice, but it didn’t look like the federal government had environmental justice on its agenda. The Reagan administration seemed to be going all-in on nuclear production while actively trying to weaken the Environmental Protection Agency. Because of these circumstances, Huegel says, the 1980s were a particularly challenging time to find support as an environmentalist.

“In the 1970s the spirit was much more bipartisan,” he says. “But in the 1980s with the election of Reagan, conservatives start to push back against environmentalism.”

But the peace activists would not be stopped. While the federal government was trying to defund and dismantle the EPA, local activists were amping up their efforts to raise awareness about the threats posed by Fernald.

In the weeks that followed the Crosby Elementary School meeting, community members Kathy and Don Meyer organized another meeting for neighbors of Fernald. The group ultimately organized as FRESH, Fernald Residents for Environmental Safety and Health, and focused on what the community — including the Fernald workers themselves — needed for a healthier life. Rather than approaching nuclear war as a black-and-white issue, they considered what actions could help those most affected by the nuclear weapons plant.

“For these reasons, [FRESH] distanced itself from the disarmament goals of the peace movement, which did not represent the conservative values of the community or the Fernald workers who made their living contributing to the nuclear deterrent,” Huegel writes in his book.

At FRESH’s second public meeting, local Rep. Tom Luken attempted to quell concerns by sharing data that showed contamination was “too low to cause acute damage,” Huegel writes. While many felt comforted by this news, one attendee, Lisa Crawford, was not satisfied. Her family’s well water had been contaminated with uranium. The problem was too personal for her to brush it off all over again.

“They didn't feel like the government was being transparent with them,” Huegel says. “Which they weren't.”

Inspired by her story and her drive for justice, Kathy Meyer invited Crawford to lead FRESH in its efforts to push for Fernald’s cleanup. They knew from the uranium leak that things were bad, and as a group they set out to demand openness and action from the Department of Energy.

Step by step, FRESH learned how to make a huge impact on local and national communities. Since they couldn’t go to the federal government for support, they formed a state coalition instead, finding support from allies like Democratic senator and former Project Mercury astronaut John Glenn, Luken and Senator Howard M. Metzenbaum.

“They worked with state politicians, they worked with the governor, they worked with the attorney general, they worked with the Ohio Protection Agency,” Huegel says. “They had some voices in Congress that were raising awareness about their issue. All of a sudden you have the state working to push back against the federal government.”

FRESH also formed national connections, joining an organization called the Military Production Network. Founded in 1987, the coalition was made up of national peace and environmental groups, as well as grassroots communities. The MPN gave FRESH more experienced people to work with and taught them how to effectively lobby for issues.

But the benefits were not all one-sided. FRESH brought grassroots credibility to this national organization by providing undeniable examples of real people affected by environmental pollution. The MPN understood that personal life stories, like that of Crawford, were the ones that could have the most impact.

“These are the people that need the microphone in their hand,” Huegel says. “This is their story.”

FRESH’s ongoing efforts and community support, as well as the momentum built by peace activists throughout the Cold War, ultimately led to the development of what was at the time one of the largest environmental clean ups in the world. After years of community pressure, in 1989, production at Fernald stopped as the Cold War began to wind down. Two years later in 1991, the Department of Energy announced the official transition from production to cleanup, and employees were offered an opportunity to stay on for Fernald’s remediation.

“As part of the unions’ latest contract, former production workers were given the training they needed to successfully transition from nuclear weapons production to environmental remediation jobs,” Huegel writes.

The Department of Energy was now in charge of a major environmental cleanup, rather than a uranium plant. They hired a private contractor, Fluor, to lead the environmental remediation efforts. And they formed citizen advisory boards, which created an open dialogue and community inclusion in decision making. This was an important change from their practices during the early Cold War.

The advisory boards discussed the challenges of the cleanup and debated potential solutions. They asked important questions, like: What does a successful cleanup look like? Where is the place of former production workers in this cleanup? After realizing that their nuclear waste would affect a community of people wherever it went, the Fernald Citizen Task Force decided to keep what they could of Fernald’s radioactive soil in their own backyard using an On-Site Disposal Facility. The most dangerous, high-level waste, which “can’t be stored in the eastern United States environment,” Huegel says, was sent to Utah and Texas.

Community input also helped decide what would become of former nuclear sites. In the case of Fernald, the community wanted a park. Funding for what would become Fernald Preserve came from a lawsuit by the State of Ohio against the Department of Energy over hazardous waste and damages to natural resources at Fernald.

“That money for damaging Ohio’s environment was repurposed into the ecological restoration at Fernald,” Huegel says.

In 2008, Fernald Preserve opened to the public, offering seven miles of trails and one of the biggest human-made wetlands in the state. As you walk its trails and stoop to admire butterfly after butterfly, it’s hard to imagine that it was once a cog in the Cold War weapon machine.

“By balancing local democratic participation and technical education with a national dialogue on environmental justice,” Huegel writes, “Fernald’s environmental movement helped forge a pragmatic solution to one of the most complex environmental challenges of the twentieth century: the radioactive legacy of the nuclear arms race.”

Lessons for the present and the future

When Huegel went for his first walk at Fernald nearly a decade ago, he knew he wanted to dig deeper. As an avid amateur birdwatcher and a public historian for the National Park Service, Fernald’s visible, fascinating history combined with its wild, natural habitats targeted all of his interests.

“I filed it away in the back of my mind that if I go back to school to do my PhD, this is what I want to study,” Huegel says. “I immediately knew Fernald was the story I wanted to tell.”

Through his research, Huegel hoped to understand exactly how humble grassroots activism could lead the way in turning a uranium plant to a healthy, hikable preserve. In his debut book — to be published July 23 by the University of Washington Press — he shares how grassroots activism succeeded then, and creates a model for contemporary grassroots activists.

Huegel’s work in Cleaning Up the Bomb Factory lays out the complicated and intricate details of one of the country’s most critical environmental mobilizations. In doing so, he underlines the pieces of Fernald’s story that could provide useful guidance in activism today and hopes that readers will find inspiration in the community activism that occurred right down the road

Like climate change, nuclear war is a question of “apocalyptic power in human hands,” Huegel points out. And talking about something as huge and catastrophic as nuclear war or climate change can feel abstract and hard to understand for the average person. But by engaging the physical spaces and local communities that are directly affected by the production of nuclear weapons, these grassroots activists made it harder for politicians and the Department of Energy to push back, or brush them off as radicals. According to Huegel, FRESH’s approach to Fernald demonstrates that approaching large, political issues through the lens of tangible, small-scale environmental activism can get results.

“I think that tangible nature of the environment is a really important lesson from environmental history,” Huegel says. “Actually engaging these systems of pollution are really helpful ways to think about big issues that can be almost overwhelming at times.”

Huegel says one thing that has complicated environmental movements throughout history is the disparity of values between white collar and blue collar workers. When environmentalists work to shut down polluting industries, they often get push back from the blue collar workers who depend on that very industry.

From the beginning, FRESH recognized that their community revolved around Fernald. There were neighbors who worked there and relied on the money for income. With that priority in mind, FRESH’s focus was never to shut down Fernald. They just wanted to clean it up.

“They had an ability to see these class issues that were in their community more easily than peace activists who, although lived close by, were kind of coming in more from the outside,” Huegel says.

FRESH knew that respecting the workers at Fernald and the conservative values of the community would be the best way to get their support. Their approach was nuanced and sophisticated and acknowledged the importance of class and labor in their community.

The story of Fernald also proves that you don’t need experience to make a difference. Crawford was not an activist when this started. Yet through FRESH, she and her allies managed to initiate a cultural transformation within the Department of Energy. FRESH’s relentless efforts and high standards finally got the Department of Energy to take responsibility for its years of nuclear pollution, and to begin cleaning up Fernald.

“These groups are fighting for their backyards and their families and the things they care about most,” Huegel says. “When you are that motivated, you will do things that will surprise you.”

Cleaning Up the Bomb Factory is out on July 23 via national and local booksellers. More info: caseyhuegel.com/cleaning-up-the-bomb-factory.

This story is featured in CityBeat's June 26 print edition.