This story is featured in CityBeat's May 15 print edition.

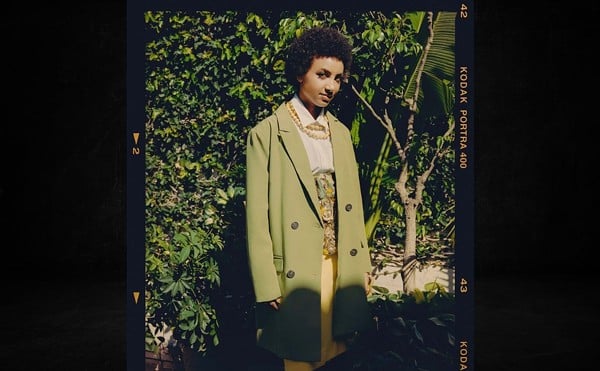

Flash forward more than 50 years and Was has done just about everything one can do in the music industry — producer of heralded albums by the likes of Bonnie Raitt, The B-52s, The Rolling Stones, Lucinda Williams and so many more; player of bass on multifarious projects, including his own band Was (Not Was); musical director of various TV shows and specials; documentary filmmaker; president of iconic jazz label Blue Note Records; and radio host.

There is also his reemergence as a live player with Wolf Brothers — a band fronted by former Grateful Dead guitarist and singer Bob Weir — which has toured off and on since 2018. And now there is the freshly minted live project Don Was and the Pan-Detroit Ensemble, which features nine members playing a mix of covers and originals that lean heavily into the jazz realm.

CityBeat recently connected with Was via a fuzzy cell phone connection to discuss how Detroit has informed his musical journey and the importance of continuing to move forward artistically and beyond.

CityBeat: Why has Detroit yielded so much interesting and dynamic music over the years?

Don Was: I think it’s that — at least in the era I grew up, post-World War II — the city attracted people from all over the world who wanted to work in the auto factories, and it was booming. They all brought their cultures with them, so you had this extreme jambalaya of all kinds of music being fused together. That becomes part of your roots — everything from polka to country to John Lee Hooker. Speaking of John Lee Hooker, I think that he captures the essence of Detroit music, and also the people who live in the city of Detroit. It’s very unpretentious, raw music. There is something about growing up in a one-industry town where everybody’s in the same boat and there is no point in putting on the airs because we know that everybody’s fate is tied to the success of the auto business. There is no point in putting a sheen on things. To me, John Lee Hooker is just about as raw as music can get without falling apart. Yet it grooves like crazy and he’s as soulful as they come. I think if you go through all genres in Detroit, whether it’s Fortune Records — Motown has some gloss to it but it’s still very raw music — MC5, The Stooges, Mitch Ryder, it’s all raw, honest music.

CB: This is a pretty short tour, so it was interesting to see that Cincinnati was one of the nine stops. Why did you want to play Cincinnati as opposed to anywhere else?

DW: It feels like Detroit. I haven’t spent a whole lot of time there but I’ve been there a few times to play. It feels like Detroit. It’s the same Midwestern, semi-industrial kind of place. The audiences are real and pretty open-minded. They’re music people. They’re not jaded. In L.A. — I’ve lived there for a long time — they see it all every day. It’s harder to turn them on.

DW: It feels like Detroit. I haven’t spent a whole lot of time there but I’ve been there a few times to play. It feels like Detroit. It’s the same Midwestern, semi-industrial kind of place. The audiences are real and pretty open-minded. They’re music people. They’re not jaded. In L.A. — I’ve lived there for a long time — they see it all every day. It’s harder to turn them on.

CB: You’re obviously known for your studio work as a producer, but what is it about playing live that still gets you going?

DW: The interchange with an audience. It’s an incredible thing that happens. The thing that re-whetted my appetite for playing was Bob Weir. The Grateful Dead audience is one of the greatest audiences in the world. Those kinds of bands, it’s all about the inner conversation between the musicians. Everybody is listening and reacting. The audience is part of it. You can feel them on the receiving end, and they send the energy back. And then the energy starts cycling. I would say it happens two or three times a night, invariably, when I played with Bobby, where everything connects, and you can feel the audience and you can feel the whole thing become one. That’s the allure of it.

DW: The interchange with an audience. It’s an incredible thing that happens. The thing that re-whetted my appetite for playing was Bob Weir. The Grateful Dead audience is one of the greatest audiences in the world. Those kinds of bands, it’s all about the inner conversation between the musicians. Everybody is listening and reacting. The audience is part of it. You can feel them on the receiving end, and they send the energy back. And then the energy starts cycling. I would say it happens two or three times a night, invariably, when I played with Bobby, where everything connects, and you can feel the audience and you can feel the whole thing become one. That’s the allure of it.

CB: You’ve talked about music being a source of joy in troubling times. Why does music resonate with us in such a visceral way?

DW: The part of the brain that processes music is activated in ways that allow us pre-language communication. We’re faced with a crazy world, and not just in troubled times politically or all kinds of natural crises. It’s tough being a human. You don’t know why you’re here. You don’t know if you or your loved ones are going to die in the next 10 seconds. You don’t know if you’re going to get fired. You don’t know if you’re going to get divorced. Anything can happen to you. It’s really tough to make sense out of it. Music helps you understand who you are and what you’re here to do. The album that’s been most helpful in my life is a Blue Note album called Speak No Evil by (jazz saxophonist) Wayne Shorter. I started listening to that when I was in college at the University of Michigan in 1970. I was pretty lost. And when I’d lose my way, when I was depressed, I put on side two of that record. When I’d listen to Wayne play, I didn’t hear the saxophone. I didn’t hear reeds or instruments; I heard the guy talking to me. He was basically telling me to keep grooving in the face of adversity.

DW: The part of the brain that processes music is activated in ways that allow us pre-language communication. We’re faced with a crazy world, and not just in troubled times politically or all kinds of natural crises. It’s tough being a human. You don’t know why you’re here. You don’t know if you or your loved ones are going to die in the next 10 seconds. You don’t know if you’re going to get fired. You don’t know if you’re going to get divorced. Anything can happen to you. It’s really tough to make sense out of it. Music helps you understand who you are and what you’re here to do. The album that’s been most helpful in my life is a Blue Note album called Speak No Evil by (jazz saxophonist) Wayne Shorter. I started listening to that when I was in college at the University of Michigan in 1970. I was pretty lost. And when I’d lose my way, when I was depressed, I put on side two of that record. When I’d listen to Wayne play, I didn’t hear the saxophone. I didn’t hear reeds or instruments; I heard the guy talking to me. He was basically telling me to keep grooving in the face of adversity.

CB: You’ve also talked about the fact that you always need to keep searching artistically. Why are you, at the age of 71, still so restless, still so interested in moving ahead?

DW: (Laughs) I don’t know, man. The minute you think you’re at the goal, you’re dead. It’s over. I took a bass lesson from (jazz great) Ron Carter a year and a half ago. He showed me something to do with my fingers. It’s so nuanced, the difference of like a millimeter and a little different angle and a little different movement. It’s microscopic but it opened up a whole universe of new approaches. That’s the other thing too — I like playing differently every night. That’s another thing I picked up from Bobby (Weir), and that’s what jazz is all about — or any kind of improvisational music — the only wrong way to play it is to play what you played last night. You want to approach it with a beginner’s mind every night and just go where it goes. It’s a new adventure every day. You’ve got to be kind of fearless about fucking it up. It’s OK. Wherever it goes, it’s not a mistake. If it goes someplace you didn’t intend it to go, keep going. That never gets old.

DW: (Laughs) I don’t know, man. The minute you think you’re at the goal, you’re dead. It’s over. I took a bass lesson from (jazz great) Ron Carter a year and a half ago. He showed me something to do with my fingers. It’s so nuanced, the difference of like a millimeter and a little different angle and a little different movement. It’s microscopic but it opened up a whole universe of new approaches. That’s the other thing too — I like playing differently every night. That’s another thing I picked up from Bobby (Weir), and that’s what jazz is all about — or any kind of improvisational music — the only wrong way to play it is to play what you played last night. You want to approach it with a beginner’s mind every night and just go where it goes. It’s a new adventure every day. You’ve got to be kind of fearless about fucking it up. It’s OK. Wherever it goes, it’s not a mistake. If it goes someplace you didn’t intend it to go, keep going. That never gets old.

Don Was plays Memorial Hall at 8 p.m. on May 25. Info: memorialhallotr.com.