The two curators end up using exactly the same words to express their enthusiasm for the beauty and craftsmanship of Tiffany glass. “I can’t get enough,” they gush in separate interviews. And as Cincinnati’s fourth Tiffany exhibit in seven years opens Saturday, the Taft Museum of Art’s Lynne Ambrosini and the Cincinnati Art Museum’s Amy Dehan believe the public feels the same way they do.

Barely half a year after the closing of Tiffany Glass: Painting with Color and Light at the Cincinnati Art Museum, the highly anticipated exhibit Louis Comfort Tiffany: Treasures from the Driehaus Collection arrives at the Taft. Ordinarily, such similar programming nearly back-to-back would be cause for concern, yet when both institutions became aware of the irreversible situation, they chose to embrace it.

“People still talk about the show that we had here (from April to Aug. 2017),” says Dehan, the CAM’s curator of decorative arts and design. “Then I mention to them that the Taft is going to have a show, too, and they say, ‘Oh, good! I’ve got to get there!’ It’s not, ‘Oh, I’ve already seen that.’ ”

The Cincinnati Art Museum’s exhibit came from the Neustadt Collection in Queens, New York. The display of 20 lamps and five windows, plus 100 samples of opalescent flat glass and “jewels” illustrating the Tiffany Studios’ palette, was the fourth-most-attended show at the museum since 2000.

Painting with Color and Light built upon the fascination following the museum’s 2011 purchase and conservation of four ecclesiastical Tiffany windows saved from the former St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church in Avondale. They went on permanent display above the Great Hall in 2012, less than a year after the Taft hosted In Company With Angels: Seven Rediscovered Tiffany Windows. That touring exhibition featured turn-of-the-20th-century treasures that were nearly forgotten after being stored in a barn in Pennsylvania many years after their rescue in 1964 from the demolished Swedenborgian Church of the New Jerusalem in Walnut Hills.

The three previous Tiffany shows whet the region’s appetite, says Ambrosini, chief curator and deputy director at the Taft. “And now we’re going to deliver more.”

The 60-plus pieces coming from Chicago’s Driehaus Museum have never been displayed outside the Windy City before. Taft is the first stop on a nationwide tour that continues into 2021. In addition to seven landscape windows, 16 lamps and 24 blown-glass vases, the exhibit includes lesser-known Tiffany items such as candlesticks, andirons, inkwells and even a chair.

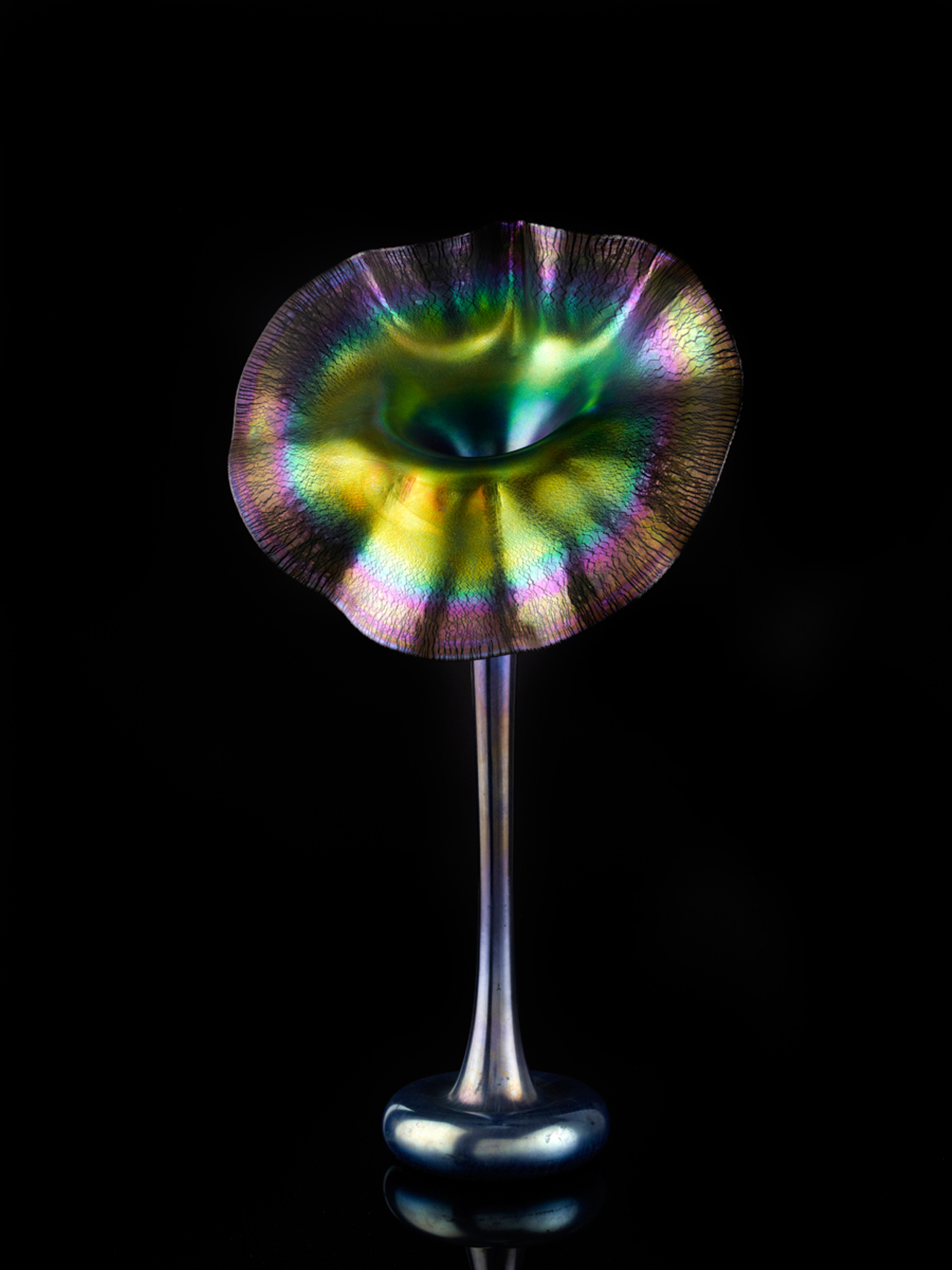

Louis Comfort Tiffany, son of the jeweler Charles Lewis Tiffany, shared his father’s entrepreneurial drive and was a masterful marketer. For example, not long after he introduced his Favrile blown glass in 1893, he approached Alfred Goshorn, the first director of the Cincinnati Art Museum, and convinced him to add his iridescent vases to the institution’s collection. But, above all, Tiffany was a painter and a perfectionist. That’s why people can’t get enough of these otherwise utilitarian objects, Ambrosini and Dehan say.

Tiffany, who was born in 1848, took the traditional Grand Tour of Europe as a young man and studied at the National Academy of Design in New York, where he exhibited his watercolors and other works.

“He trained as a painter, but he was also just entranced by glass and how light could flow through the glass, and the special effects that created,” Dehan says.

But rather than continue the Old World traditions of painting on glass, Tiffany set out to paint with glass. When he couldn’t find all the colors, opacities and textures he wanted from existing suppliers in the United States, he hired one of the most talented glass chemists in England and brought him to America to open his own operation in Corona, N.Y. Tiffany would walk the floor to select the precise pieces that his crew of male and female artisans would use in a lamp or window, and would order them to swap out sections.

“He didn’t settle for ‘just OK.’ It had to be perfect,” Dehan says. “Say they were looking for the drapery of a figure’s coat, and they wanted the wrinkles to run just so. If that passage of glass was in the middle of the sheet, they’d cut into the middle of it.” Cost and waste were not concerns as Tiffany Studios determined the décor for the Gilded Age.

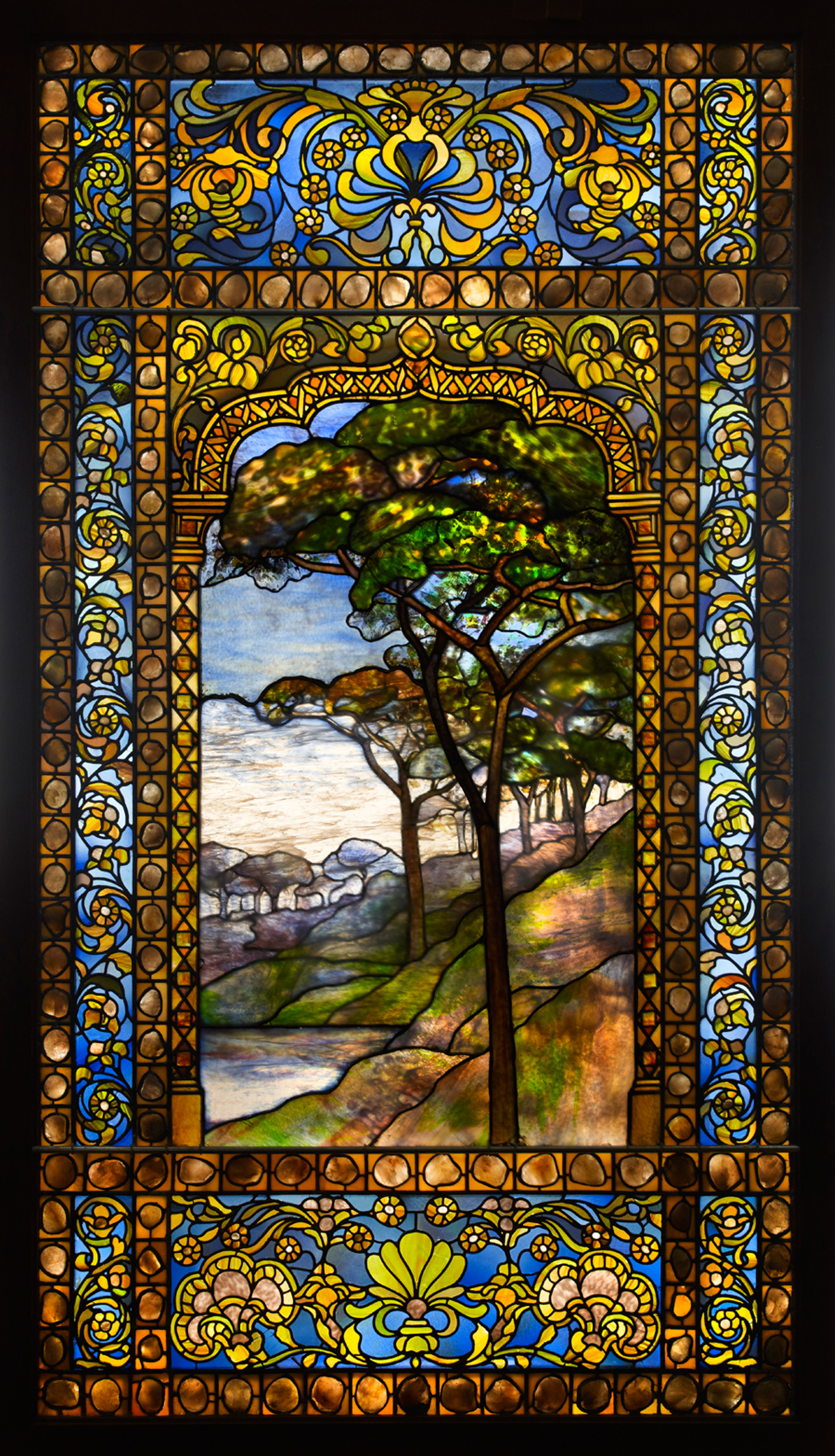

As Ambrosini leafs through a book of Tiffany’s many creations in metal, wood and glass, even a flat photograph conveys the sublime beauty of one of his rippling, multilayered landscape windows.

“There’s still a lingering prejudice against decorative arts as compared to fine arts,” she says. “But someone who does landscapes in glass is still a landscape artist, and he is, in my opinion, at his greatest in the landscape windows.”

She points to a detail image of sun-dappled foliage. “This is a painter,” Ambrosini says, noting the level of craft, care and artistry in all of Tiffany’s furnishings. “We just rarely see in the orbit of our daily lives objects as refined, as beautiful, as these. It’s just very seductive, and it’s very hard not to sigh with pleasure.”

Yet Tiffany glass fell out of favor in the 1920s and ’30s, with lamps cast off to secondhand shops as the sinuous, nature-inspired designs of Art Nouveau gave way to the modern lines of Art Deco. Tiffany Studios went bankrupt in 1932. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the style became popular again. T.G.I. Friday’s hung faux Tiffany lamps in its restaurants, and Richard Driehaus put a real Tiffany window — the first purchase of his collection — in his own bar in Chicago a few years later.

Forward to 2018, and museum curators and visitors still want more.

“It’s Tiffany!” Dehan says. “Who can’t have enough of Tiffany?”

Louis Comfort Tiffany: Treasures From The Driehaus Collection opens Saturday at the Taft Museum of Art, 316 Pike St., Downtown. Through May 27. Tickets/more info: taftmuseum.org.