These 20 Historic Signs Around Town Tell the Story of Cincinnati

By Katherine Barrier on Fri, Jul 19, 2024 at 12:55 pm

Books and articles may be your go-to sources to learn more about Cincinnati's history, but peppered around the city are historic markers and signs that can really help you envision the historic events and moments that took place in these spots. Whether a president stood in the exact spot you're standing in to give an unprecedented speech or you're among the remains of a once vibrant village of Ohio's Indigenous people, these signs can help you connect with the place and time in a way you can't anywhere else.

From a historic hotel that was ranked as one of the best in the world to murals and statues depicting Black Cincinnatians' struggle for equality, here are 20 historic markers around town that share the story of the Queen City. You can also find and read more historic signs at the Historical Marker Database.

From a historic hotel that was ranked as one of the best in the world to murals and statues depicting Black Cincinnatians' struggle for equality, here are 20 historic markers around town that share the story of the Queen City. You can also find and read more historic signs at the Historical Marker Database.

Scroll down to view images

The Black Brigade of Cincinnati

Where you can find the marker: At Sawyer Point (705 E. Pete Rose Way), just east of the Purple People Bridge in downtown Cincinnati.

The history: In 1862, Cincinnati officials, worried about an invasion from Confederate troops, ordered Cincinnati citizens to form home guards. But when a group of Black men stepped in to volunteer, they were turned away and, instead, police began rounding up Black men and forcing them into service. Outraged by the treatment of these men who were willing to support the Union, the commander of the Department of Ohio sent Major General Lewis Wallace to liberate the men and command the civilians. Under the command of Judge William Martin Dickson, the Cincinnati Black Brigade, the first Black unit with a military purpose in the Civil War, was formed. In September of 1862, the Brigade, made up of about 1,000 members, worked to clear forests and build fortifications, military roads and rifle pits. The unit received praise for their work and disbanded when Southern forces no longer threatened the city. Members later fought with other Black regiments, including the 127th Ohio Volunteer Infantry.

Photo: Cameron Knight

Herzog Studio/Hank Williams at Herzog

Where you can find the marker: Just outside CityBeat’s office at 811 Race St., Over-the-Rhine.

The history: Cincinnati’s first commercial recording studio, Herzog Studio, was opened on the second floor of CityBeat’s building in 1945 by brothers “Bucky," a WLW radio engineer, and Charles Herzog, making the Queen City the place to record country music before Nashville came calling. The studio worked with artists and musicians from WLW and King Records and stars like Hank Williams, Pattie Page and The Delmore Brothers. Herzog even cut Williams’ “Lovesick Blues,” the song that launched Williams to superstardom and earned him an invite to the Grand Ole Opry.

1 of 20

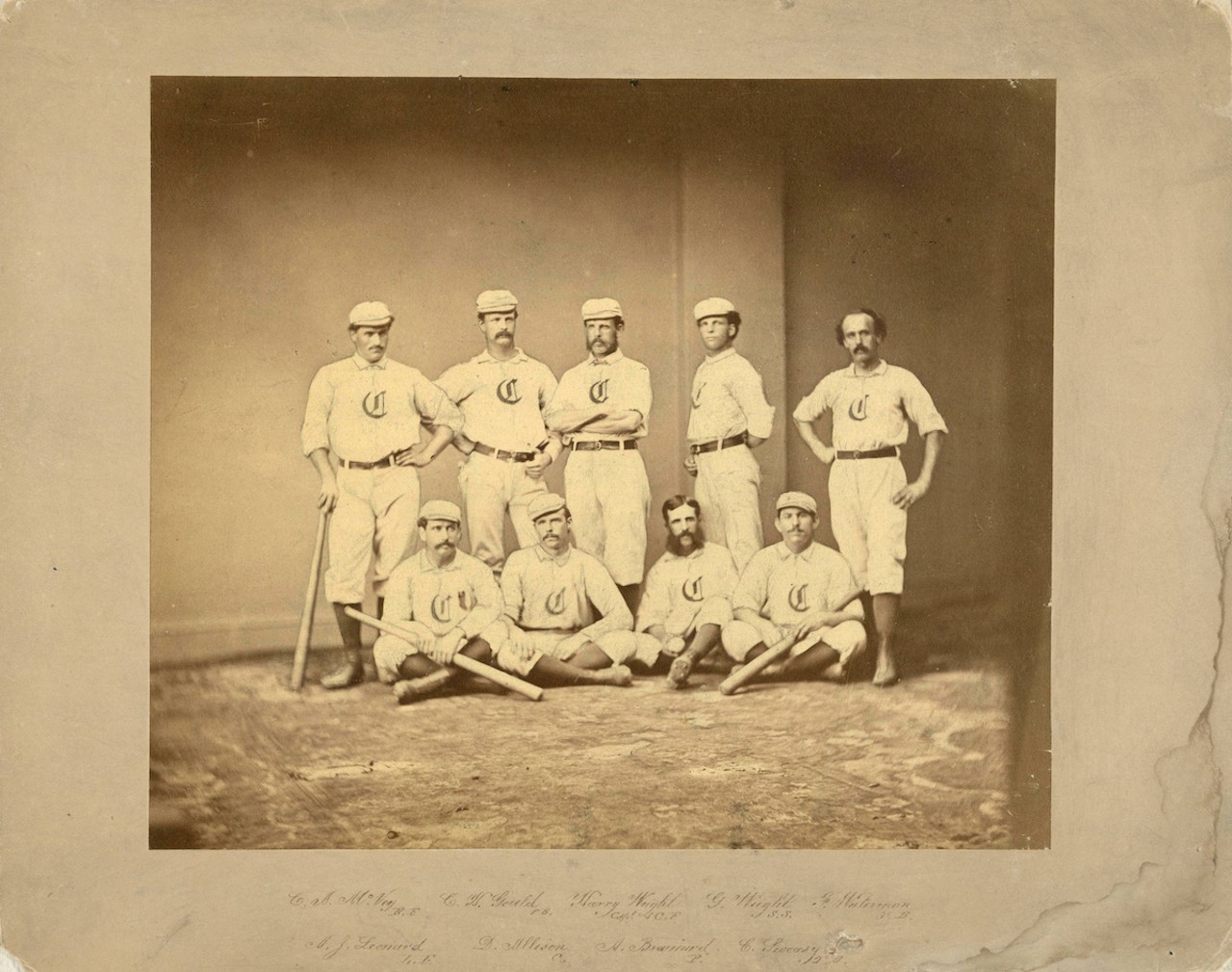

The Home Field of Pro Baseball’s First Team

Where you can find the marker: On the grounds of the Cincinnati Museum Center (1301 Western Ave., West End), to the right of the fountain as you’re walking toward the building.

The history: In the 19th century — before there was Union Terminal and long before there was the Cincinnati Museum Center — there was the West End’s Lincoln Park, a sprawling public space with a lake, gazebo and ball park called Union Grounds. Union Grounds was located where the museum is and was the home to the first pro baseball team, the Cincinnati Red Stockings, founded in 1869. The ball park could seat up to 4,000 people, but it’s estimated that big games would draw around 12,000 people to the grounds. The team disbanded in 1870 and Cincinnati would see two more franchises of the same name form. The one that we know as the Cincinnati Reds today was founded in 1881.

3 of 20

Photo: Hailey Bollinger

King Records

Where you can find the marker: Near 1540 Brewster Ave., Evanston.

The history: King Records is America’s music history. Owned by Syd Nathan, the record label operated from 1943 to 1971 and introduced many to musicians in genres ranging from bluegrass and country to R&B, soul and funk. Stars like James Brown, the Stanley Brothers, Cincinnati’s own Bootsy Collins and many more recorded at King Records during its history. The marker was placed at the former studio building in Evanston in 2008 by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame + Museum and the City of Cincinnati.

4 of 20

Photo: Brewster Rhoads

Marian Spencer

Where you can find the marker: In Smale Riverfront Park (166 W Mehring Way, Downtown), east of the Roebling Bridge and west of the circular maze.

The history: A local Civil Rights icon, Marian Spencer led the fight to desegregate Coney Island in the ‘50s after her children wanted to attend an event there, but it was not open to Black children. Following that, Spencer spent the rest of her life fighting for racial equality. She chaired the Cincinnati NAACP Education Committee for 20 years, championing educational equity in schools. She was also the first woman to be the president of the Cincinnati chapter of the NAACP, became the first African American woman Cincinnati City Council member and served as vice mayor. In Smale Riverfront Park, you’ll find a wall dedicated to Spencer with the inscription, “Be smart, be polite, and keep on fighting.” Underneath that reads off Spencer’s accomplishments: “Led the desegregation of Coney Island. • First African-American woman elected to Cincinnati City Council. • Fought to desegregate public schools.” A statue of Spencer by sculpturist Tom Tsuchiya was also placed in the park in 2021.

5 of 20

The Sultana

Where you can find the marker: At Sawyer Point (705 E. Pete Rose Way), just east of the Purple People Bridge in downtown Cincinnati.

The history: Nearly 160 years later, the tragedy that struck the Sultana remains the U.S.’s worst maritime disaster. The wooden steam transport was constructed at the John Lithoberry Shipyard in Cincinnati in 1862 and was used after the Civil War to transport freed federal prisoners north from the Confederate stockades. The ship was only meant to carry 376 people, but on the night of April 27, 1865, over 2,300 Union soldiers were aboard when a steam boiler exploded. The ship was engulfed in a fireball and sank in the Mississippi River, just 10 miles north of Memphis. That night, 1,700 people died, including 791 Ohioans and 194 Kentuckians. About 50 of those people killed were believed to be Cincinnatians.

6 of 20

Photo: Provided by americanart.si.edu

Robert S. Duncanson

Where you can find the marker: Just outside the Taft Museum of Art (316 Pike St., Downtown).

The history: If you’ve ever been to the Taft Museum of Art and admired the murals on its walls, you can thank this man: Robert S. Duncanson. Duncanson was the first African American artist to reach international acclaim, overcoming the extreme racial prejudice of his time to become the “best landscape painter in the West” and paving the way for other people of color to become professional artists. Born in New York in 1821, Duncanson moved to Cincinnati when he was around 18 and was later commissioned by Cincinnati arts patron Nicholas Longworth to paint murals in his home, now the Taft Museum. The photo above shows Duncanson’s work, Landscape with Rainbow, painted in 1859 and on display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The marker dedicated to the painter was installed in 2003 by the Ohio Bicentennial Commission, Cinergy and the Ohio Historical Society

7 of 20

Photo: Hailey Bollinger

Site of Abraham Lincoln’s Speech in Cincinnati

Where you can find the marker: On the building at 100 E. Fifth Street in downtown Cincinnati, right by Government Square.

The history: In 1858, Abraham Lincoln lost the race for a U.S. Senate seat in Illinois to Stephen A. Douglas, but the race, which featured the famous Lincoln-Douglas Debates, catapulted the future president into the political spotlight. By September of the next year, Douglas was trying to make inroads with Ohio Republicans and making speeches throughout the state. Lincoln would visit each city following Douglas to deliver remarks rebutting Douglas’ recent statements in Harper’s Weekly regarding congressional authority and states’ rights when it came to slavery. Lincoln gave his speech in Cincinnati on Sept. 17, 1859, from a balcony along Fifth Street where Government Square is now located. A plaque marking the moment was later installed by the Ohio Lincoln Sesquicentennial Committee.

8 of 20

Site of John F. Kennedy’s Speech in Cincinnati

Where you can find the marker: On the building at 101 E. Fifth St. in downtown Cincinnati, across the street from Government Square and where Lincoln made his speech.

The history: Of all the eerie similarities between presidents Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy, they also share one connected by Cincinnati. Just across the street from where Lincoln famously spoke, JFK made his own speech on Oct. 8, 1962. On a platform on Fifth Street looking out on Fountain Square, JFK stumped for the re-election of Ohio governor Michael DiSalle and spoke about the importance of electing Democratic Ohio representatives so the country could progress in health care, housing, education and employment. You can listen to the remarks here.

9 of 20

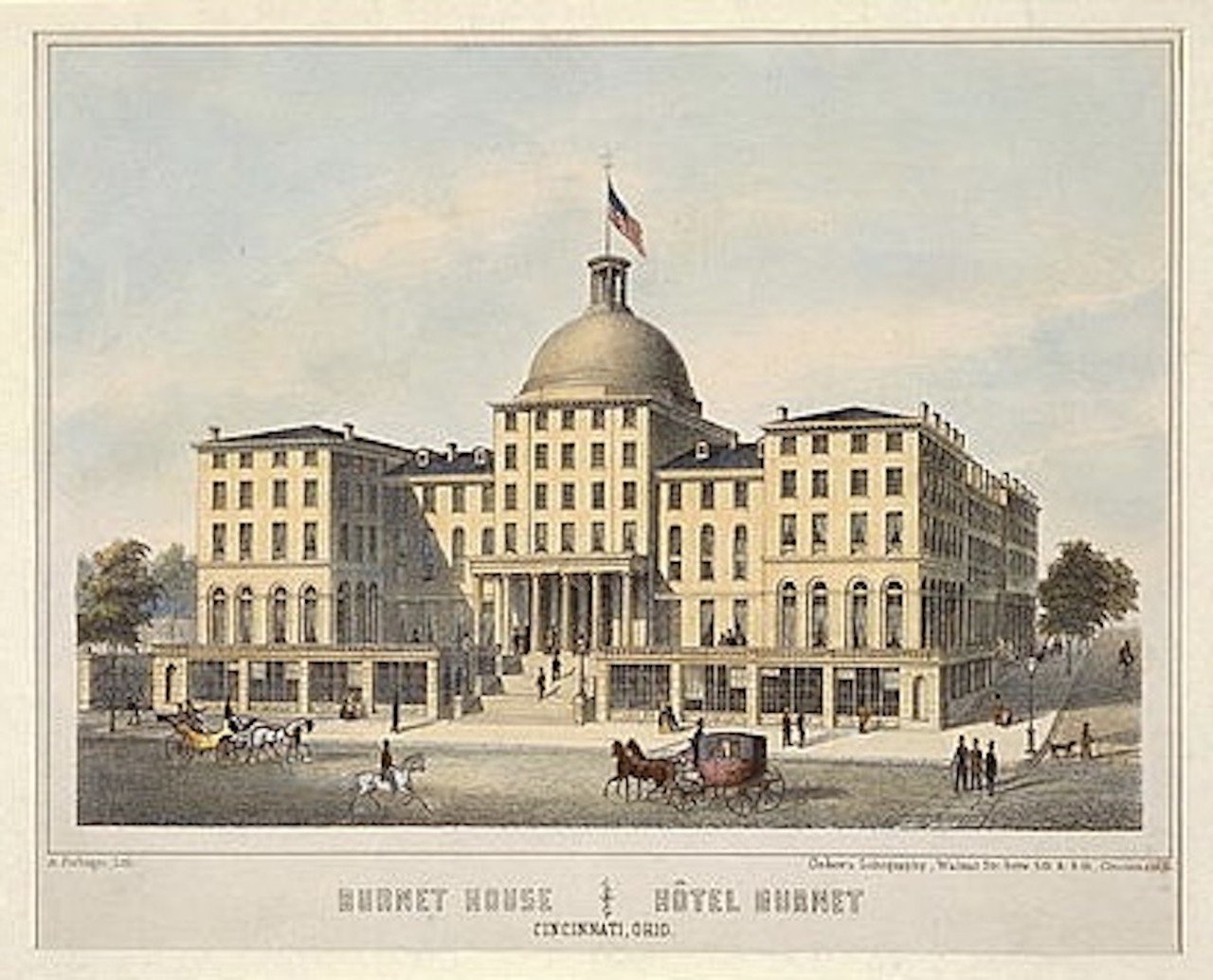

The Burnet House

Where you can find the marker: The intersection of Vine and Third streets in downtown.

The history: If Michelin stars existed for hotels in the 1800s, the Burnet House would’ve garnered all of them. This grand hotel opened at the corner of Third and Vine streets downtown on May 30, 1850. It featured 340 luxury rooms and was at the time considered one of the best hotels in the world. Famous people like Abraham Lincoln, who gave a speech from the hotel’s balcony in 1861; Edward VII, Prince of Wales; and Swedish opera singer Jenny Lind all stayed here. The hotel was shuttered and demolished in 1926.

10 of 20

Elizabeth Blackwell

Where you can find the marker: At the intersection of Ninth and Walnut streets on the YMCA building downtown.

The history: Elizabeth Blackwell was the first woman in the United States to earn a medical degree. Born in Bristol, England, in 1821, Blackwell and her family moved to the United States when she was around 11, settling in Cincinnati. She went into teaching after her father died to help support her family, but wanted to go into medicine after a dying friend told her a female physician would have made the experience easier. Blackwell was rejected from every medical school she applied to, except Geneva College in rural New York. Although her acceptance letter there had turned out to be intended as a practical joke, Blackwell graduated first in her class. Blackwell opened her own clinic for poor women and a medical college in New York City. She was the physician who popularized hand-washing among doctors after noticing male doctors tended to cause epidemics by not washing their hands between patients. The marker was erected in 2003 by the Ohio Bicentennial Commission, The International Paper Company Foundation and The Ohio Historical Society.

11 of 20

Photo: w_lemay/Wikimedia Commons

Miller-Leuser Log House

Where you can find the marker: Near 6540 Clough Pike, Anderson Township.

The history: This log house, named after the first and last families to own it, in Anderson Township is one of the only surviving structures built by Ohio River Valley settlers, and it’s on the same site where it was built. Ichabod Benton Miller built the home around 1796 and it remained occupied for the next 170 years. Anderson Township bought the house in 1971.

12 of 20

Photo: w_lemay/Wikimedia Commons

Clark Stone House

Where you can find the marker: At the intersection of Clough Pike and Hunley Road in Anderson Township.

The history: The Clark Stone House is one of the oldest standing stone homes in Ohio. James Clark constructed the two-story limestone house along Clough Creek in 1801 after his family moved to Anderson Township several years prior. In his lifetime, Clark was a drummer at the Battle of Yorktown; worked as a mathematician, teacher, justice of the peace, judge and state legislator; and he ran a distillery and operated and orchard nursery. In 1864, it was sold to the Leuser family, followed by the related Messmer family in 1923 and finally to the township in 1995.

13 of 20

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

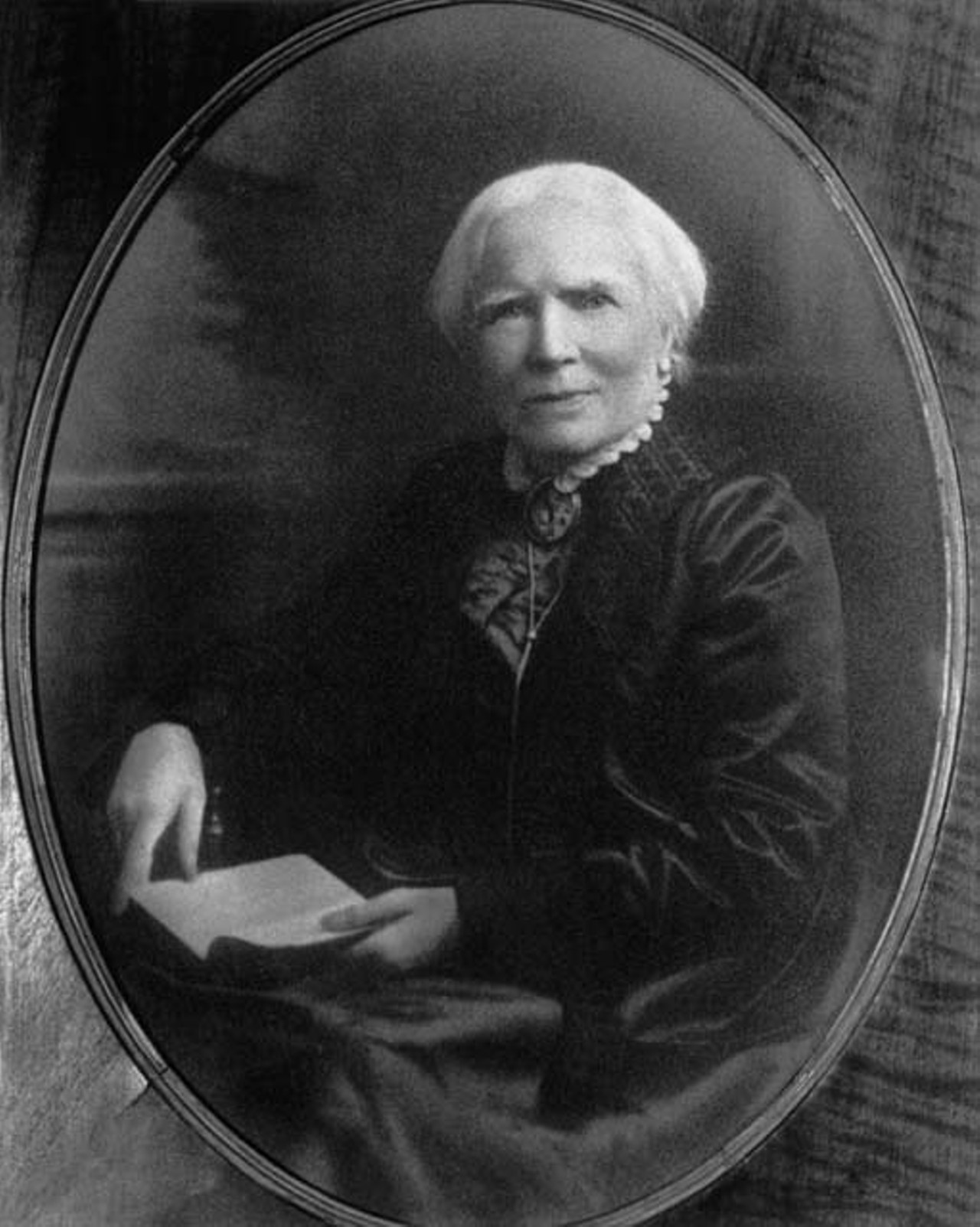

Votes for Women

Where you can find the marker: Near 2902 Gilbert Ave., Walnut Hills.

The history: This Walnut Hills marker honors the Women’s Suffrage movement, particularly wife and husband Lucy Stone (pictured) and Henry Blackwell, who helped found the American Woman Suffrage Association. The couple lived in a small brick home in Walnut Hills from around 1846 to 1856 when they moved east. They returned in 1885 to speak at the Woman’s Rights Convention in Cincinnati. The marker was installed on Gibert Avenue in 2022 by the William G. Pomeroy Foundation.

14 of 20

Photo: artworkscincinnati.org

Tribute to J.P. Ball

Where you can find the marker: Near 400 Race St., Downtown.

The history: J.P. Ball defied the odds of his time and overcame adversity and racism to become a photographer at a time when the medium was new technology and slavery was still legal in the U.S. Ball was born a free Black person in Virginia in 1825 and studied under another free Black photographer, John B. Bailey, before opening his own studio in Cincinnati. While that studio didn’t last, Ball would go on to build his career in other cities before returning to Cincinnati in 1849 to open a new studio and gallery, Great Daguerrean Gallery of the West, which saw great success. Throughout his career, Ball took thousands of photographs, including of famous people like Queen Victoria, Charles Dickens, Frederick Douglass and the family of Ulysses S. Grant. He also used his platform to speak out against slavery.

15 of 20

Photo: Lydia Schembre

Cincinnati’s First Place of Worship

Where you can find the marker: Near 150 E. Fourth St., Downtown.

The history: While the Federal Reserve Bank building now sits here, this site at the corner of Fourth and Main streets was formerly home to the first place of public worship in Cincinnati. The wood-frame church was erected in 1792 and was called the Cincinnati Presbyterian Church. Rev. James Kemper was installed as its first minister, making him the first minister ordained in Ohio. Jacob Burnet, a judge and early Cincinnati settler described the church as “enclosed with clapboards, but neither lathed, plastered or ceiled. The floor was made of boat-plank, laid loosely on sleepers. The seats were constructed of the same material, supported by blocks of wood. They were, of course, without backs; and here our forefather pioneers worshiped, with their trusty rifles between their knees."

16 of 20

Photo: Casey Roberts

Findlay Market Opening Day Parade

Where you can find the marker: Outside Great American Ball Park at 100 Joe Nuxhall Way, Downtown.

The history: Nobody does Opening Day quite like Cincinnati, but to be fair, we’ve been doing our parade and celebrations to mark the beginning of the Cincinnati Reds’ season for over 100 years. The annual Findlay Market Opening Day Parade got its start in 1920 after the Reds won the World Championship the year before. Fans gathered at Findlay Market for the first parade, and the rest is history. It became an annual tradition featuring marching bands, horse-drawn wagons and fans, or “rooters,” as they were called. While the tradition might have changed a little bit over the last century, the enthusiasm for the parade remains as strong as ever.

17 of 20

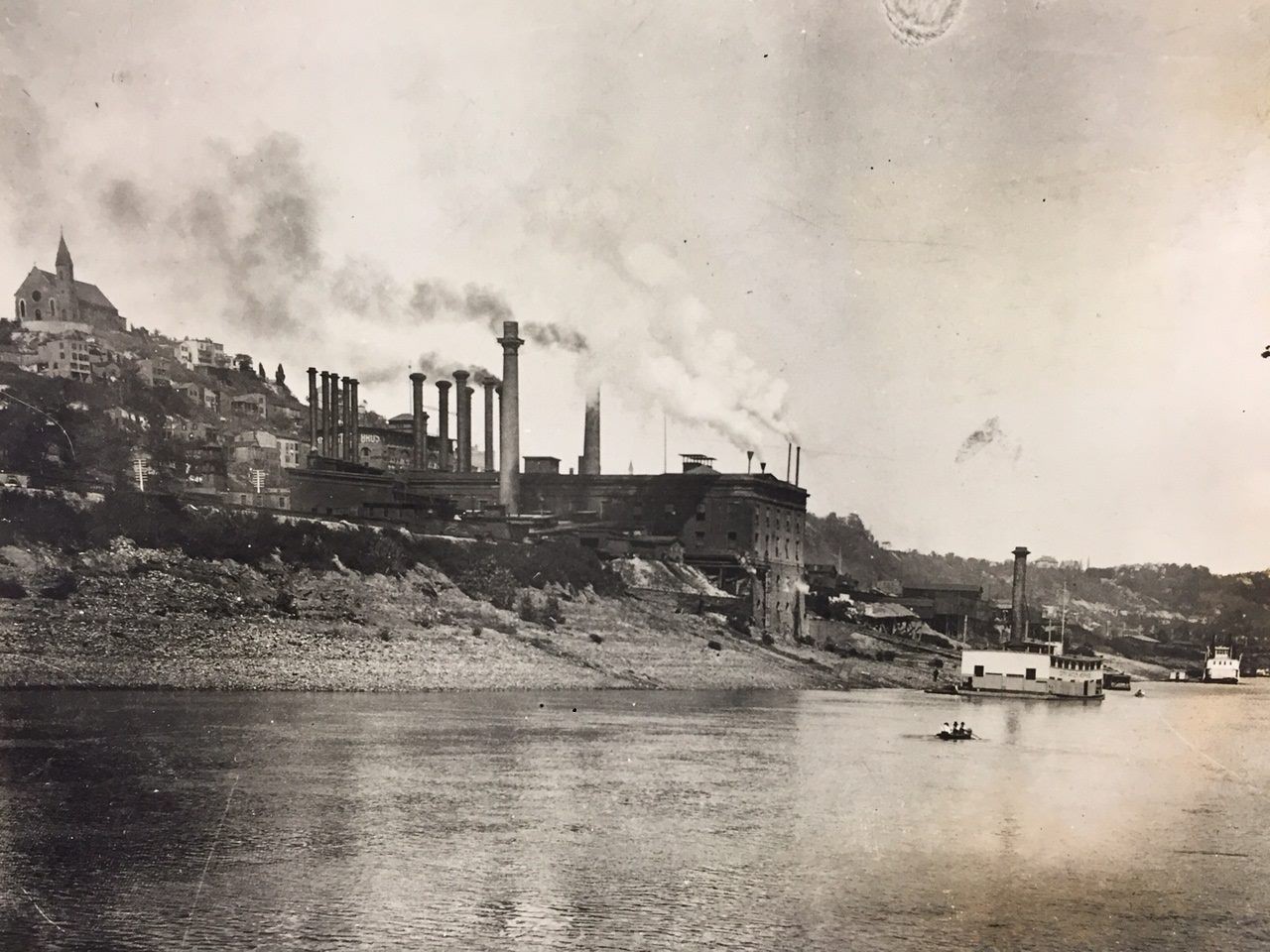

Ohio’s First Publicly Owned Water System

Where you can find the marker: At Sawyer Point (705 E. Pete Rose Way, Downtown), along the riverfront and near the tennis and pickleball courts.

The history: Starting in 1821, Cincinnati’s water supply came from a privately owned company. But in 1839, the city purchased the company following a vote from Cincinnati residents and authorization from the Ohio State Legislature. On June 25, 1839, Greater Cincinnati Water Works became the first publicly owned water system in the state. At the site of the marker in what’s now Sawyer Point, Water Works used two steam pumps, three-and-a-half miles of iron piping and 19 miles of wooden piping to provide the city with a million gallons of water every day. Front Street Pumping Station, replacing the earliest facilities, opened on the same site in 1865 and operated there until 1907. The ruins of the facilities can still be seen at Sawyer Point.

18 of 20

Photo: Nyttend/Wikimedia Commons

The Madisonville Site

Where you can find the marker: In a small park at the very end of Mariemont Avenue in Mariemont.

The history: A place once so abundant in artifacts it was nicknamed “pottery field,” the Madisonville site is the largest and most studied villages of the Fort Ancient people, who inhabited the area from around 1450 to 1670. Archaeologists from Harvard trained at the site from 1879 to 1911, and doctor and archaeologist Charles Metz, with help from Harvard anthropologist Frederic Ward Putnam, excavated the remains of the village, uncovering houses, storage pits and burials. Town planner John Nolen designed a pavilion to honor the site, but it wasn’t built until 2001.

19 of 20

Photo: Holden Mathis

First Glass Door Oven

Where you can find the marker: In Camp Washington at the intersection of Spring Grove Avenue and Straight Street.

The history: The first full-size glass door oven was invented by Ernst H. Huenefeld in Cincinnati in 1909. The glass window allowed bakers to see their food cooking in the oven without having to open the door. The Cincinnati Preservation Association and The Ohio Historical Society erected this marker in 2003.

20 of 20

Related Slideshows

- Local Cincinnati

- News & Opinion

- Arts & Culture

- Things to Do

- Food & Drink

- Cannabis

- Music

- Cincinnati in Pictures

- About City Beat

- About Us

- Advertise

- Contact Us

- Work Here

- Big Lou Holdings, LLC

- Cincinnati CityBeat

- Detroit Metro Times

- Louisville LEO Weekly

- Sauce Magazine